Rows: 4,568

Columns: 36

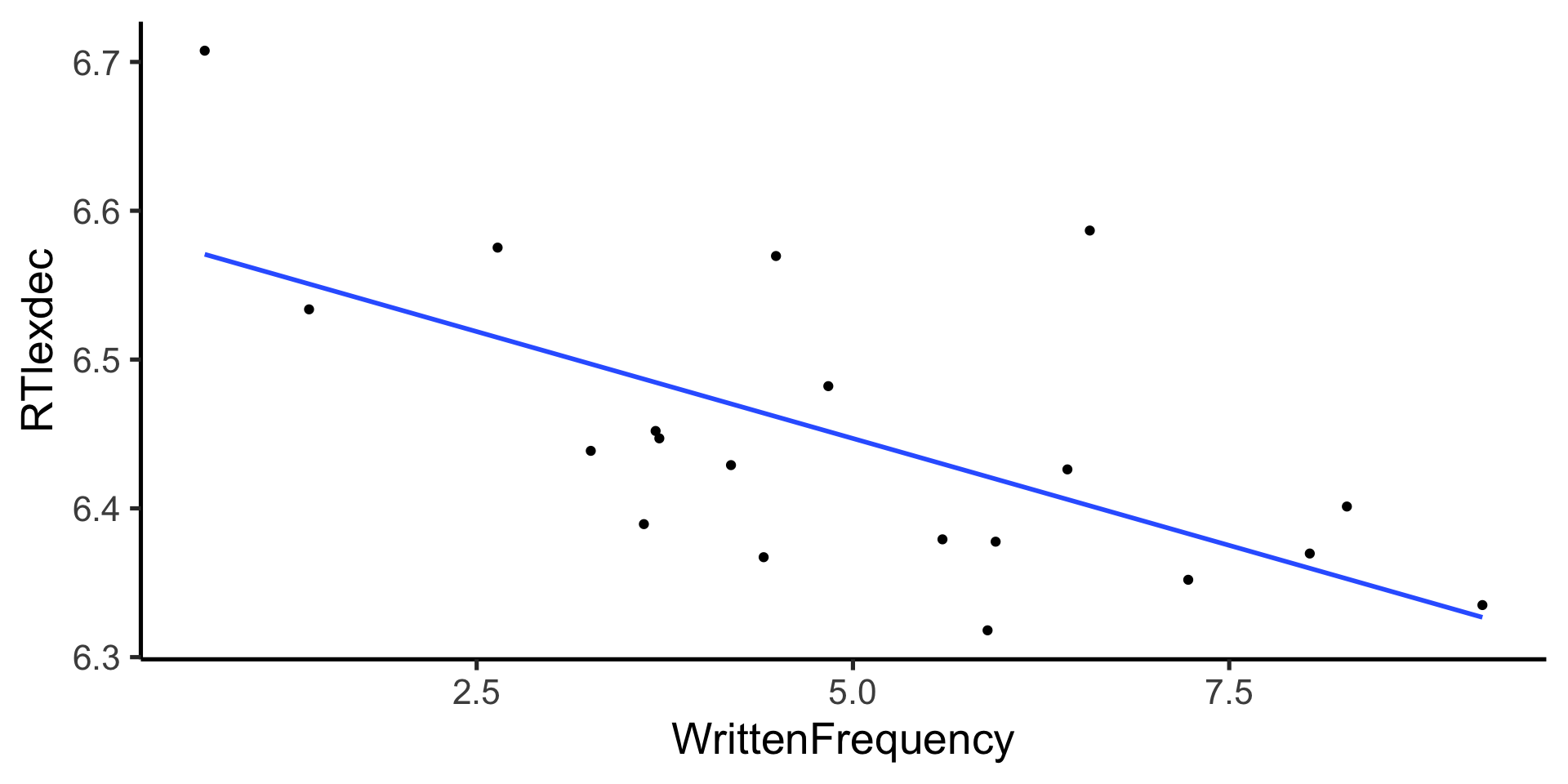

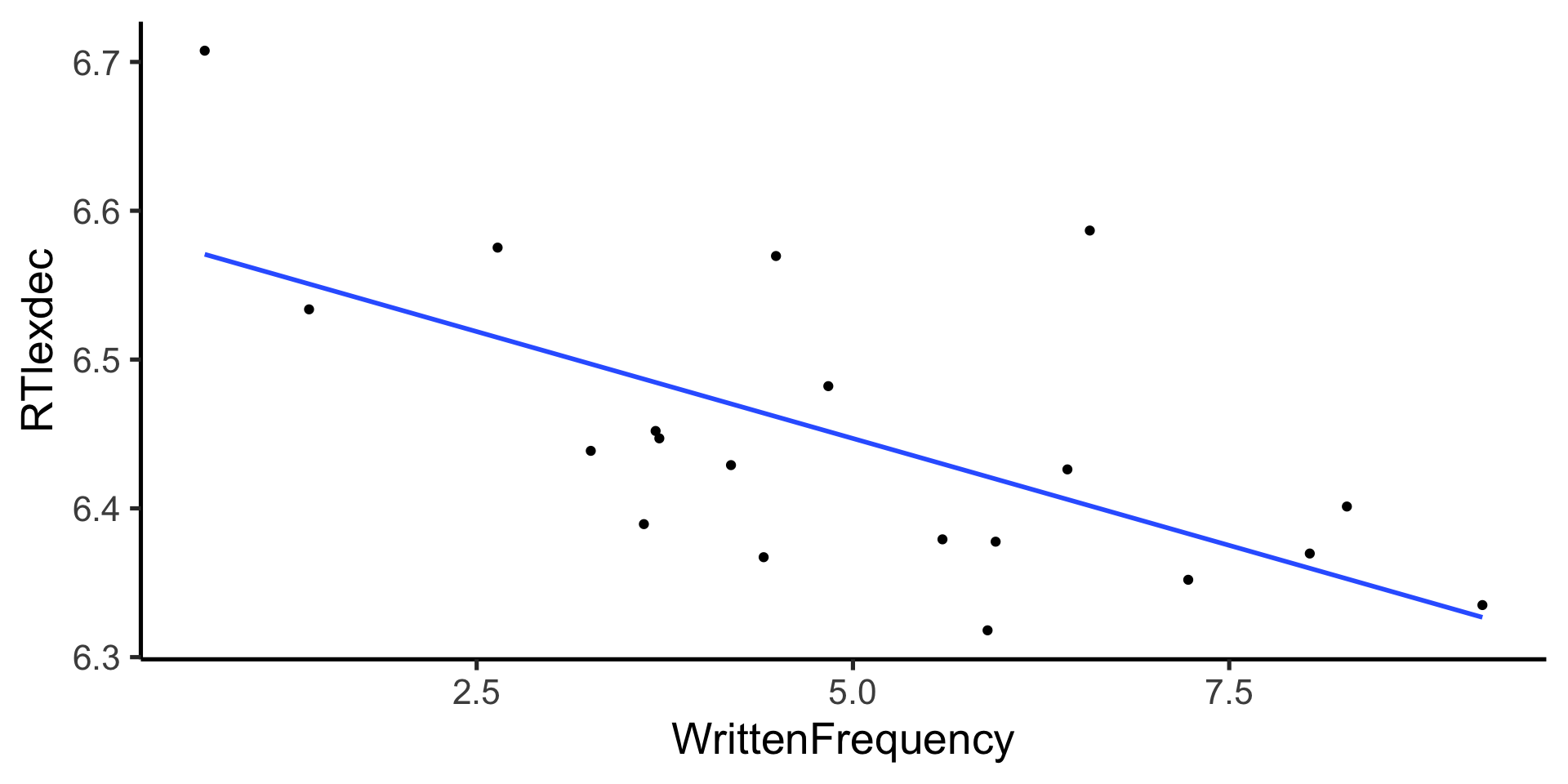

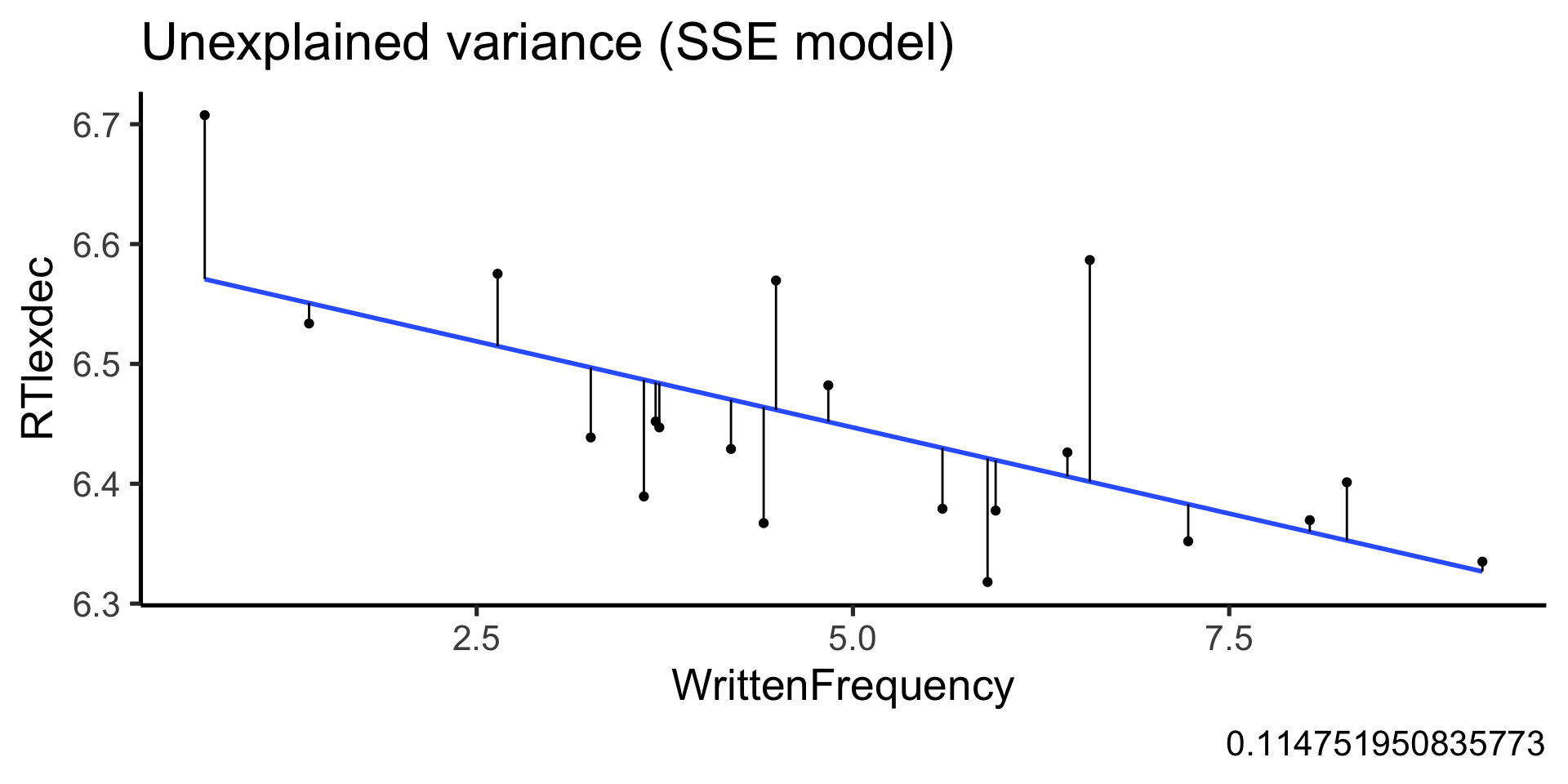

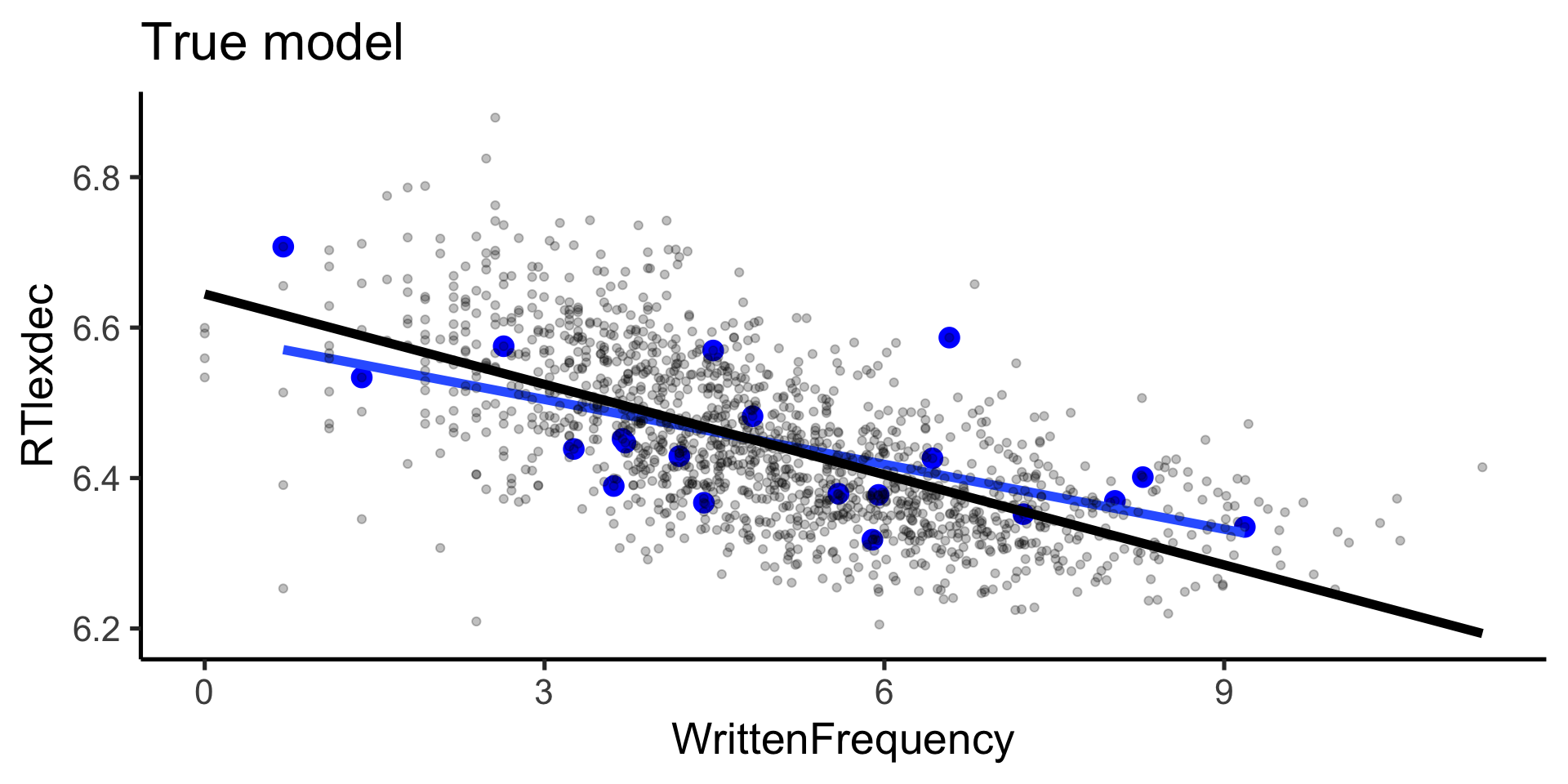

$ RTlexdec <dbl> 6.543754, 6.397596, 6.304942, 6.424221…

$ RTnaming <dbl> 6.145044, 6.246882, 6.143756, 6.131878…

$ Familiarity <dbl> 2.37, 4.43, 5.60, 3.87, 3.93, 3.27, 3.…

$ Word <fct> doe, whore, stress, pork, plug, prop, …

$ AgeSubject <fct> young, young, young, young, young, you…

$ WordCategory <fct> N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N, N,…

$ WrittenFrequency <dbl> 3.9120230, 4.5217886, 6.5057841, 5.017…

$ WrittenSpokenFrequencyRatio <dbl> 1.02165125, 0.35048297, 2.08935600, -0…

$ FamilySize <dbl> 1.3862944, 1.3862944, 1.6094379, 1.945…

$ DerivationalEntropy <dbl> 0.14144, 0.42706, 0.06197, 0.43035, 0.…

$ InflectionalEntropy <dbl> 0.02114, 0.94198, 1.44339, 0.00000, 1.…

$ NumberSimplexSynsets <dbl> 0.6931472, 1.0986123, 2.4849066, 1.098…

$ NumberComplexSynsets <dbl> 0.000000, 0.000000, 1.945910, 2.639057…

$ LengthInLetters <int> 3, 5, 6, 4, 4, 4, 4, 3, 3, 5, 5, 3, 5,…

$ Ncount <int> 8, 5, 0, 8, 3, 9, 6, 13, 3, 3, 1, 9, 1…

$ MeanBigramFrequency <dbl> 7.036333, 9.537878, 9.883931, 8.309180…

$ FrequencyInitialDiphone <dbl> 12.02268, 12.59780, 13.30069, 12.07807…

$ ConspelV <int> 10, 20, 10, 5, 17, 19, 10, 13, 1, 7, 1…

$ ConspelN <dbl> 3.737670, 7.870930, 6.693324, 6.677083…

$ ConphonV <int> 41, 38, 13, 6, 17, 21, 13, 7, 11, 14, …

$ ConphonN <dbl> 8.837826, 9.775825, 7.040536, 3.828641…

$ ConfriendsV <int> 8, 20, 10, 4, 17, 19, 10, 6, 0, 7, 14,…

$ ConfriendsN <dbl> 3.295837, 7.870930, 6.693324, 3.526361…

$ ConffV <dbl> 0.6931472, 0.0000000, 0.0000000, 0.693…

$ ConffN <dbl> 2.7080502, 0.0000000, 0.0000000, 6.634…

$ ConfbV <dbl> 3.4965076, 2.9444390, 1.3862944, 1.098…

$ ConfbN <dbl> 8.833900, 9.614738, 5.817111, 2.564949…

$ NounFrequency <int> 49, 142, 565, 150, 170, 125, 582, 2061…

$ VerbFrequency <int> 0, 0, 473, 0, 120, 280, 110, 76, 4, 86…

$ CV <fct> C, C, C, C, C, C, C, C, V, C, C, V, C,…

$ Obstruent <fct> obst, obst, obst, obst, obst, obst, ob…

$ Frication <fct> burst, frication, frication, burst, bu…

$ Voice <fct> voiced, voiceless, voiceless, voiceles…

$ FrequencyInitialDiphoneWord <dbl> 10.129308, 9.054388, 12.422026, 10.048…

$ FrequencyInitialDiphoneSyllable <dbl> 10.409763, 9.148252, 13.127395, 11.003…

$ CorrectLexdec <int> 27, 30, 30, 30, 26, 28, 30, 28, 25, 29…